Whilst sometimes it is hard to make sense of horses, they have five senses like us.

A recent scientific study, referenced at the bottom of the page, has summarised current evidence of how horses experience the world around them.

Both humans and horses can see, hear, smell, taste and touch. The acuity of the senses are not the same, so horses and humans perceive the same environment differently.

Vision

Vision

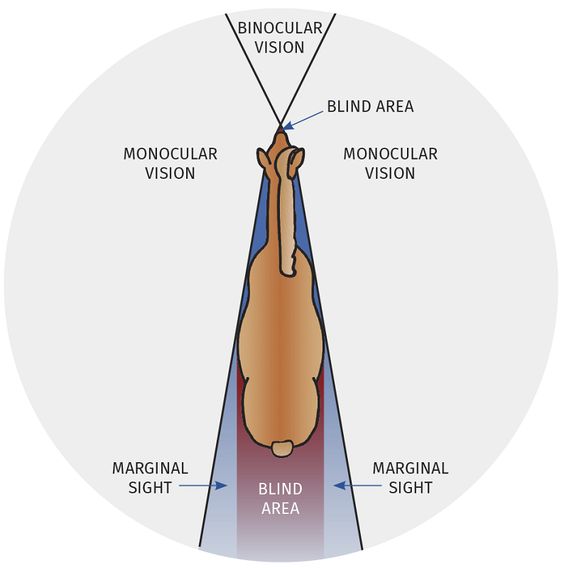

Horses evolved on open grasslands, where they needed to be alert to predators, so a panoramic view was more helpful. Horses have a field of vision that is narrow and wide, with a small blind spot to the rear.

The binocular field of vision (seen by both eyes) is only 55 – 65o in front of the horse compared to 120o in humans. The anatomy of the horse’s retina also provides a visual strip to see the horizon, but not so much in the sky or on the ground. So a horse will rotate its eyeball and move its head around to adapt to these deficiencies. Being able to move the head freely is important to the horse.

The horse’s pupils readily dilate in low light conditions and the eye has a reflective inner lining (tapetum). These both help a horse’s night vision, which is much better than humans, and a horse’s vision is better on overcast than bright sunny days.

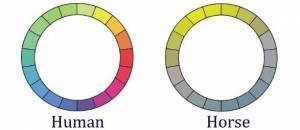

Horses have colour vision the same as red/green colour-blind humans. Reds, greens, browns and oranges are not distinguishable, and neither are blue from purple hues.

Horses have colour vision the same as red/green colour-blind humans. Reds, greens, browns and oranges are not distinguishable, and neither are blue from purple hues.

Horses have a natural preference to look closely at things on their left side, which is probably why horsemanship has developed with mounting, leading, bridling et cetera from the near (left) side.

Hearing

A horse will rotate its ears in the direction of a sound and the funnel shape assists sound detection.

The audible frequencies for horse and humans do not entirely overlap, with horses able to detect far higher frequencies but not as good as humans at low frequencies.

This extended range at high frequencies makes horses different to other large mammals and explains why a horse might be reactive to something that a human cannot hear. This could include ultrasonic rodent repellents, so a horse’s reactions to these should be monitored if they are introduced to a horse’s environment.

A horse can recognise its familiar humans and stable mates from sound alone, which explains why a horse might call to his mate who has left the stable.

Hearing ability does weaken with age but other senses adapt. Several researchers have conducted experiments to try to determine what type of music horses prefer - classical music or instrumental guitar seem to be good choices.

Smell

The Flehmen response is when a horse raises its head, curls its lip and inhales. It helps the horse get a better sense of something interesting in the air.

There have been very few studies of the sense of smell in horses, but we know that stallions do not rely on smell to detect a mare ready for mating, rather her behaviour gives the signal.

Horses can identify other horses by smell and these individual compounds are mostly a component of hair.

There is a genetic basis so a horse may recognise its relatives. If a person is handling several horses in turn, the scent of the last horse may be detected by the next horse, so in this situation it would be better to handle any aggressor in the group last.

Taste

Horses are able to detect sweet, sour, salty and bitter tastes, but relies less on smell to assess flavour than humans do. There is individual variation in taste preferences but horses do select foods based on nutrient profile, not just taste.

Touch

The skin is the largest sensory organ in horses, as well as humans, and it is the primary mode of communication between human and horse.

Areas such as the muzzle, neck, withers, coronets, shoulders, lower flank and rear of the pastern are typically more sensitive.

The epidermis on the face is thinner and sensitivity is very high around the eyes, nostrils and mouth. A horse’s whiskers are rich in nerve supply and important sense organs, so they should not be trimmed or removed. The use of tight nosebands in equestrian sport is also a source of pain and stress to the horse.

Grooming or mutual grooming between horses and human to horse is a positive behaviour. The area around the withers is a favourite spot and scratching this area drops the heart rate in horses. Foals like scratching around the tail. Providing a reward to horses by scratching their favourite spots reduces reliance on food rewards and helps with training.

Horse massage is increasingly popular and regular massage has been demonstrated to benefit horses in low to moderate stressful situations.

The response to massage is most likely mediated by oxytocin as it is with massage in humans and other mammals. Wither scratching, eye and face rubbing can lower the stress response in horses simultaneously exposed to unpleasant sounds.

Horses react readily to unpleasant touch by foot stomping, tail switching, ear flicking, head shaking and biting.

A horse will learn to avoid the electric fence as electric shocks from fences, jiggers and prodders are particularly painful.

The use of the twitch applied to an area rich in nerve endings inflicts pain and distracts the horse from the injection or other painful procedure. Whilst it immobilises the horse it can also give rise to an explosive panic response, so handlers need to be alert.

All horses are different and there are individual variations in the acuity of the senses. A better understanding of how a horse might react helps the safety and welfare of both horses and the people who work with them.

References:

Maria Vilain Rørvang, Birte L. Nielsen, Andrew N. McLean. 2020. Sensory abilities of horses and their importance for equitation science Frontiers in Veterinary Science (in press) https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.00633/abstract